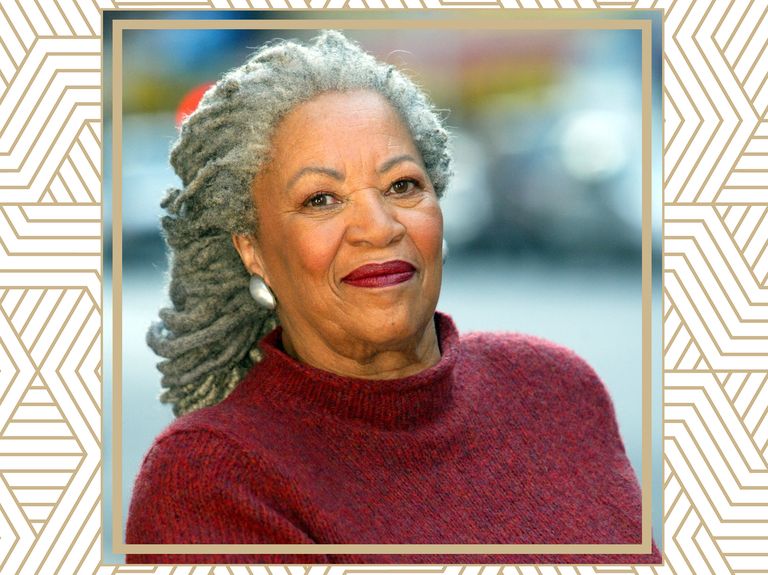

I met Toni Morrison when she was deep into her 80s — a delicious time to meet any human, but especially one as free as Morrison. After my three aunts, who were born in a sharecropper’s home on the outskirts of sugar cane fields in the Caribbean, Morrison was hands down one of the freest and blackest women I’d ever met. At 86, she was in complete possession of herself, but I suspect that she was for a very long time. Just take a listen to past television interviews where the prize-winning novelist satisfyingly shreds arrogant journalists to pieces when they dared to ask imprudent questions.

When I interviewed her for The Pieces I Am, the artful documentary about her life and art, I got to engage with her exceptional mind and beautiful heart for two days. She had zero pretenses and didn’t hold back. She was generous and filled with mischievous wit and a steely and sharp intellect. The Nobel Prize-winning author who blessed us with The Bluest Eye, Sula, Song of Solomon, Beloved, Tar Baby, Home, Love, Desdemona, and many other literary gems, was revered the world over. And everyone was pounding at her door, asking for interviews, advice, or just a moment of her time. So she had to safeguard her privacy with astute gracefulness, like the women in her riveting novel Jazz. I still wonder if she was writing about her own challenges when she wrote about the dilemma faced by the characters that inhabited the novel’s imaginary urbanscape: “Hospitality is gold in this city. You have to be clever to figure out how to be welcoming and defensive at the same time.”

When she invited me to visit with her after the interviews, I understood the honor and the sophisticated space I was entering.

Whenever I visited Morrison, I hit a button in my mind to record the precious moments we shared. Her laugh, in particular, was a beauty to behold — it sounded like a rainforest river cascading down a mountain, crashing through boulders, sweet and thunderous, sexy and coy. It was refreshing. I delighted in her takedowns of rich people and the moneyed elite. Despite her ascent on the global stage and her financial success, Morrison remained loyal to the working class and poor folk — the same men, women, and children she exalted in her epic novels. While she was regal, for sure, Morrison never lost her homegirl swagger.

Her eye rolls were ferocious whenever a certain president came on the screen. “Turn it off,” she’d shout, “he’s infecting my television.” I’ve yet to meet anyone who gives more cutting shade or deadlier side-eyes than Morrison did.

Several months after the interviews for the documentary, Morrison asked me to visit with her for her 87th birthday. What does one wear to celebrate a queen on her day? A blue teal blouse emblazoned with peacock feathers because I knew she loved birds, of course. Birds are everywhere in her books and she used them to tell classic parables. Like in her divine Nobel Prize acceptance speech when she opened with a story about an old, blind black woman being goaded by children who asked her if the bird they were holding in their hands was alive or dead. Morrison told the crowd, "I choose to read the bird as language and the woman as a practiced writer. The question the children put to her: ‘Is it living or dead?’ is not unreal because she thinks of language as susceptible to death, erasure; certainly imperiled and salvageable only by an effort of the will." In her powerful speech, Morrison cautioned against "oppressive language,” which she argued “does more than represent violence; it is violence, does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge.” But in the end, Morrison wondered if the children's question was merely a straightforward one, because "if the old and wise who have lived life and faced death cannot describe either, who can?”

The simple answer is that Morrison could — and she did so for more than 50 years.

Her 87th birthday was quiet, a sunny and chilly winter day. We sat in one of her rooms, sharing food, sharing stories. Just the two of us. Her son Ford was just leaving as I was arriving for lunch. She was comfortable in grey cashmere pajamas and Ugg slippers, luxuriating in her multi-tiered gorgeous boathouse located on the banks of the Hudson River. In addition to the feathery blouse, I also wore a blush wide brim Fedora and black boots. She told me that I resembled an Australian aborigine. Ha! When I asked her why she chose to skip a birthday party — so many of her friends wanted to throw her a bash — she told me she preferred the quiet birthdays, spent in reflection and solitude.

As much as she belonged to the world, Morrison belonged to herself. Her sovereignty was contagious. She told me she liked it better being in her own company, surrounded by things she loved — trees, the majestic river, books, birds and her beloved houseplants. She had many phone calls that afternoon, and at one point, the phone kept interrupting her stories. She asked her nurse — a Caribbean woman about whom she said, “Could you believe she didn’t know who Angela Davis was?" when she introduced us — to put the phone away.

“Shush that annoying thing-y,” Morrison said, handing over her bedazzled smartphone. She had elegant hands, which she used to write all her books in longhand on a legal pad. Her nails were always gorgeously manicured, and her birthday nails were the color of the moment — a deep, dark red creamy hue.

Birthday greetings would go straight to voicemail that day. She would later listen and enjoy and also spill the tea of all the celebrities who called. Morrison enjoyed the attention, which she embraced on her own terms. When she quieted the phone because she wanted to be present, I remembered the words of a wise shaman who once told me that the greatest gift we can give each other is to be present. Morrison gave me a most precious gift each time I visited with her, and I understand this was her gift to all who knew her.

Fresh flowers, including the bouquet I brought, perfumed her grand home — a sophisticated four story palace decorated with gorgeous art, including a stunning Romare Bearden piece, large portraits of her sons and family, and framed mementos. A used napkin with her red lips, which was autographed by Gabriel Garcia Marquez adorns one wall. The Nobel Prize letter hangs inside her guest bathroom and it is sandwiched between an autographed photo of Muhammad Ali and a letter from a Texas correction facility alerting her that her novel, Paradise, was banned because it could cause a prison riot.

The Queen of Letters built her castle with windows facing the river one searing and exquisite sentence at a time, never compromising or holding back. She was free of the master gaze and showed us how we could be too. She wrote to free us, invoking her own wisdom: "The function of freedom is to free someone else."

On the ride to her house, I found the loveliest peach lilies the color of the morning light in a Fort Green, Brooklyn flower shop owned by a sweet Japanese couple. Morrison adored them and asked me to place the glamorous flowers at the footstool by her bed. “So I could see them when I wake up, so I could smell them while I dream," she said.

I noticed a stunning black and white photograph of a naked woman, soft caramel skin, sporting a short soft Afro on the wall near her bed. The model was sitting on the floor with her sinewy back to the camera, her hands were raised high above her head and she held a globe. Like Hercules, the black woman in the photo had super strength and held the world in her hands. When I peered closely, the model looked like a young Toni. I returned to “her sick room,” which is what she called a small bedroom with views of the majestic river (in fact, every room in her boathouse had views of the famed river) and where we sat that afternoon, and inquired about the fabulous picture.

“Is that you naked in that photo in your bedroom?” I asked.

“Wasn’t I hot, though?” she responded with a twinkle in her eye. “I only got paid five bucks for it. I should’ve asked for more.” She told me the photo was taken around 1956, when she was 25-years-old, by a woman photographer whose name she’d long forgotten when she was teaching English at Texas Southern University. The photographer was creating a series on the female body and was looking for models and asked Morrison. She described the experience as fun — it was art, and also, why not?

Morrison had always been free.

Visiting Morrison felt like I was visiting my mother. The two women, born continents and a decade apart, shared many things, including a love of the natural world and the night sky. They would’ve been sister-friends had they been born near each other, they are root women, and from a generation where you breastfed your neighbor’s babies while she ran her errands, no questions asked. (Morrison took time away from her own writing to finish her friend Toni Cade Bambara’s novel, These Bones are Not My Child, a book about the unsolved Atlanta child murders in the 1980’s, because Cade Bambara died before she could finish the book.) Both momma and Morrison are from a generation of women when sister-friends meant everything to each other and when being in community was the only way to survive.

On birthdays, my mother usually regales me with my birthing story so I was curious to learn Morrison's. Morrison, the second of four children, told me that she was born at home with a midwife. I will never forget why: “In those days only prostitutes gave birth in hospitals,” she said. “Prostitutes had no other place to go.”

I felt a motherly loveliness with Morrison. And she felt comfortable, too. That day we talked about almost everything: junk food (she loved Trader Joe’s cheddar puffs), sex (she thought it was important to enjoy it with your husband or anyone you please, married or not). When I told her I found Brazilian men sexy she agreed, telling me about the time she visited Sao Paolo. "Fine, fine men," she said. "Black cowboys on the pampas was a sight to behold." When I told her it’s too bad I won’t get to experience one when I travel there one day, she asked why not? I said that I am married, to which Morrison quipped, "It’s just an experiment.” She cackled. We talked about the importance of sister-friends. She said that Angela Davis had just visited her and cooked what she said was a no-chicken chicken, which I guess was vegan, and she said it tasted “surprisingly good." But, she noted, “Angela was more fun when she smoked and drank and ate real chicken.”

Toni Morrison was so much fun. She had a lightness to her, and if she wanted to, she could fly.

When Morrison was more mobile she said one of her profound joys, equal to writing, was gardening. She was a plant mother to several gorgeous geraniums and a slew of giant jades. One in particular was her pride and joy. “This one,” she said, pointing to a four-foot bush, "came from a cutting from Nelson Mandela’s jade."

I bought her carrot cake, from a celebrated New York City bakery, and she blew a candle revealing her wish, “to be less achy.” The carrot cake did not pass her muster —not enough carrots, she said. I savored every word that came out of her witty, beautiful, and brilliant mouth that day, knowing that this was a gift for my self-actualization. Though her work and legacy looms large and will continue to heal, empower, and inspire generations to come, Morrison had at least one more book left and I wish she would’ve stayed with us just a little bit longer to see it through.

Morrison’s books were vitamins for us. Her body of work decolonized generations; her superb craft inspired three generations of writers and artists. Morrison's work informs my writing and my art each day. Producing a film about her life strengthened me and it fills me with joy to know that younger generations who’ve never read her books will want to pick one up after watching her honest and intimate interviews at the center of the film. Spending time with Morrison in person, and celebrating her 87th birthday, was a final flourish. I got to hang out with Chloe Ardelia Wofford, the Lorain, Ohio homegirl who rocked the literary canon with truth-telling like no other.

Sandra Guzmán is an EMMY award-winning journalist, author, and documentary filmmaker. She was one of the producers and lead interviewer in the film, Toni Morrison: The Pieces I am. She is author of the feminist self-help book for Latinx women, The New Latina’s Bible. Sandra was editor of Heart and Soul and Latina magazines and associate editor at the New York Post. Her media work amplifies and celebrates stories and histories of communities and people at the margins of American life. Follow her on Twitter @mssandraguzman.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY