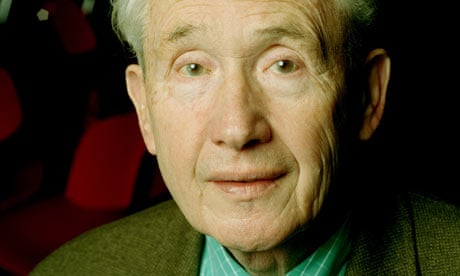

Frank McCourt, whose evocative tales of a poverty-stricken Irish childhood enthralled readers around the world and sparked the genre of "misery lit", has died of cancer in a Manhattan hospice aged 78.

Born in New York, he was the eldest of seven children born to Irish immigrant parents who later returned to Ireland, where they slipped ever deeper into poverty during the 1930s.

After returning at the age of 19 to the US city, where he worked as schoolteacher, he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1997 for his memoir, Angela's Ashes, which described a gut-wrenchingly impoverished upbringing in Limerick.

McCourt's description of begging, stealing and battling with an alcoholic father struck a chord on both sides of the Atlantic, although it ruffled feathers in Ireland where some took exception to his depiction of wartime life on the west coast.

His brother, Malachy McCourt, also a successful writer, announced McCourt's death last night. McCourt had been fighting meningitis for some time but was recently diagnosed with metastatic melanoma, a punishing form of skin cancer.

A teacher for 30 years in New York's state school system, McCourt turned to writing late in life and found success with what he described as "an epic of woe".

A swift bestseller which sparked its own literary genre of tales of hard-bitten childhoods, Angela's Ashes opened with the memorable line: "Worse than the ordinary miserable childhood is the miserable Irish childhood, and worse yet is the miserable Irish Catholic childhood."

In the book, McCourt recounted wearing ragged clothes, struggling with ill-health, absent parents and unsympathetic teachers against a backdrop of an ever-present Catholic church in "the lanes" – the slum district of Limerick in the 1930s and 1940s. McCourt lost three of his six siblings to early deaths in childhood, fought typhoid himself and was driven to petty crime for survival.

He told one interviewer that he waited until he was in his 60s to begin writing because it took him many years to overcome the demons of his childhood: "I had to get rid of the anger in my system before I could write."

Ironically, the book brought him fame and wealth. It allowed him to buy a luxurious home in Connecticut, where his neighbours included Dustin Hoffman and Arthur Miller. The director Alan Parker made a movie version of Angela's Ashes in 1999, casting Robert Carlyle and Emily Watson in lead roles.

To mixed reviews, McCourt followed that book with two subsequent memoirs – 'Tis in 1999 and Teacher Man in 2005, which described his life in New York.

But his depiction of the Ireland of his upbringing, which he described as "a terrible place, a backwater", angered critics in the country of his birth.

Some accused him of exaggerating the conditions of his childhood, which he strenuously denied – once telling the Observer: "What can I say except that it all happened?"

On one occasion, signing books at a shop in Limerick, McCourt was confronted by a furious customer who ripped up Angela's Ashes, declaring: "You're a disgrace to Ireland, the church and your mother!"

Irrespective of the controversy, McCourt's books racked up sales of more than 10m copies in the US alone. In a statement last night, Carolyn Reidy, president of McCourt's publisher, Simon & Schuster, said: "We have been privileged to publish his books, which have touched, and will continue to touch, millions of readers in myriad positive and meaningful ways."

McCourt had been unwell for some time and had undergone chemotherapy. After a period of remission, he reportedly fell ill again while on a cruise in the Pacific and spent time at a hospital in Tahiti, before travelling home to New York.

Twice divorced, McCourt is survived by his third wife, Ellen Frey, by a daughter and by three grandchildren.

Angela's Ashes: an extract

"My father and mother should have stayed in New York where they met and married and where I was born. Instead, they returned to Ireland when I was four, my brother, Malachy, three, the twins, Oliver and Eugene, barely one, and my sister, Margaret, dead and gone.

When I look back on my childhood I wonder how I managed to survive at all. It was, of course, a miserable childhood: the happy childhood is hardly worth your while.

Worse than the ordinary miserable childhood is the miserable Irish childhood, and worse yet is the miserable Irish Catholic childhood.

People everywhere brag and whimper about the woes of their early years, but nothing can compare with the Irish version: the poverty; the shiftless loquacious alcoholic father; the pious defeated mother moaning by the fire; pompous priests; bullying schoolmasters; the English and the terrible things they did to us for eight hundred long years. Above all – we were wet. Out in the Atlantic Ocean great sheets of rain gathered to drift slowly up the River Shannon and settle forever in Limerick.

The rain dampened the city from the Feast of the Circumcision to New Year's Eve. It created a cacophony of hacking coughs, bronchial rattles, asthmatic wheezes, consumptive croaks. It turned noses into fountains, lungs into bacterial sponges.

It provoked cures galore; to ease the catarrh you boiled onions in milk blackened with pepper; for the congested passages you made a paste of boiled flour and nettles, wrapped it in a rag, and slapped it, sizzling, on the chest."